Every day, when MegAnne Offredi, general manager of the Holiday Inn & Suites-Bellingham Airport, sits down at her desk, she braces for fresh news about growing hostility between the United States and Canada that's driving down revenue and bookings at her hotel.

In the first three months of this year, her hotel in Bellingham, Washington — just 20 miles southeast of the U.S.-Canada border — saw a 22% year-over-year drop in room revenue, plus 29% and 34% declines in restaurant and bar sales, respectively. All in all, the hotel, which sold around 2,500 fewer rooms in the first quarter compared to the same time last year, has suffered a 28% drop in total revenue, Offredi said.

Border crossings between Canada and Washington state have declined by half, according to data from the British Columbia Ministry of Transportation and Washington state’s Department of Transportation. Crossings have dropped from 216,000 in March 2024 to 121,000 vehicles last month, the Vancouver Sun reported. Flight bookings and short-term rentals also have dropped, according to CoStar reporting.

The decline in travel comes from dissolving relations between the two countries, fueled by President Donald Trump's tariff policies and comments on annexing Canada as the 51st U.S. state.

While new Canadian taxes were not mentioned on Trump's "Liberation Day" on April 2 — when he announced a blanket 10% tariff on all foreign imports as well as additional measures for select countries — Canada already was in the crosshairs. As of press time, the U.S. tariffs on Canada call for a 25% tax on Canadian steel, aluminum and cars. Energy and potash have a 10% tariff, and all other goods unless part of the North American Free Trade Agreement carry a blanket 25% tax.

Canada's Prime Minister Mark Carney announced his own 25% tax on U.S. car imports in retaliation.

Offredi knows that as bad as tensions between the countries seem today, they could get even worse and have deeper effects.

“If the partnership between U.S. and Canada dissolves any further, it’s going to be extremely negative," Offredi said.

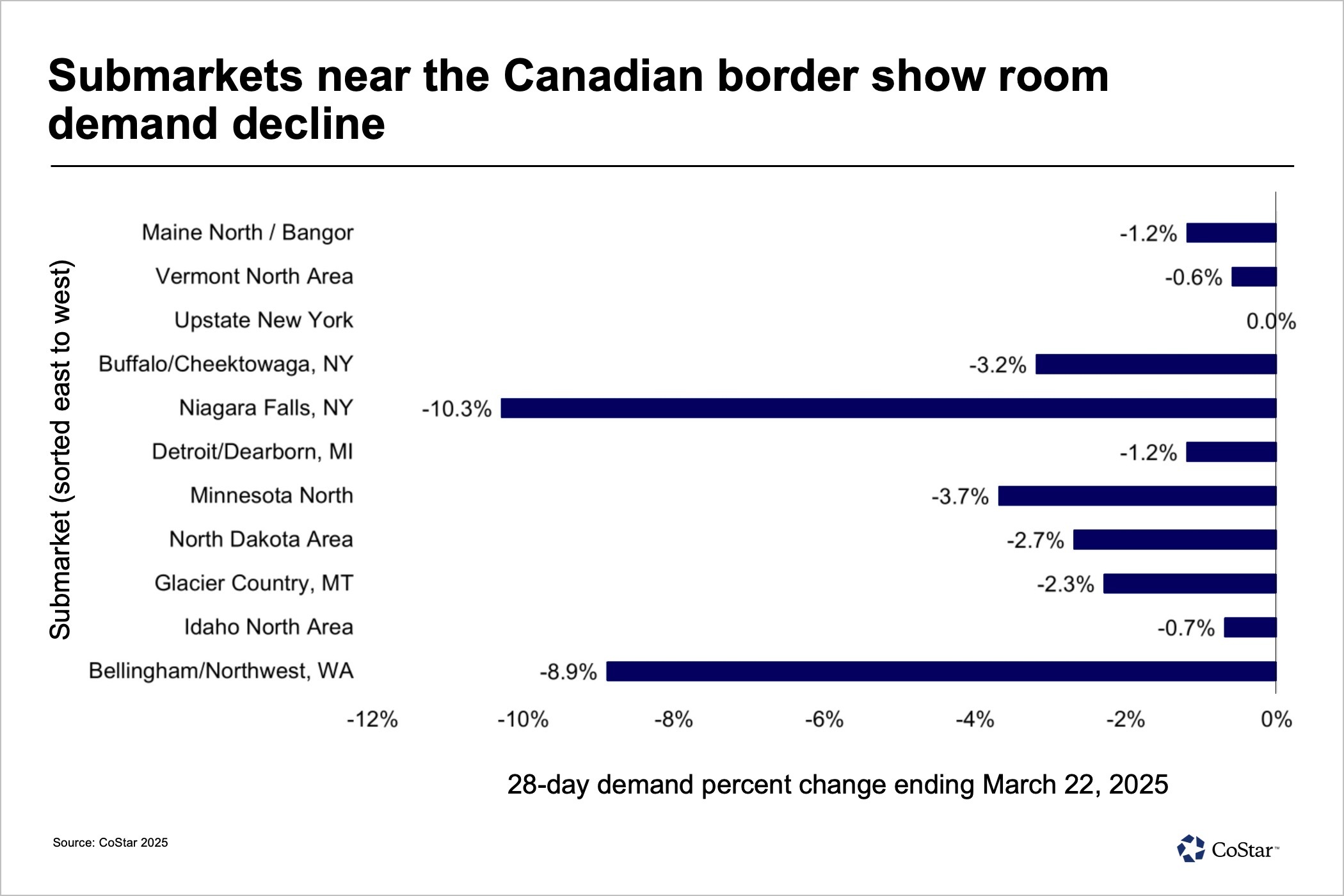

According to CoStar hospitality data for the 28-day period ending March 22, markets along the Canadian border saw declines in room demand as steep as 10.3% in Niagara Falls, New York, and 8.9% in the Bellingham/Northwest Washington region.

Jan Freitag, national director for Hospitality Market Analytics at CoStar, said he's kept a close eye on these numbers since the November U.S. presidential election. On Inauguration Day, once it became clear tariffs would be a central part of the Trump administration's early actions, Freitag said he started looking at weekly hotel performance in the U.S./Canada border markets.

Saturdays were an early indicator that these tense relations were having an effect on hotel business, Freitag said. Saturday night hotel stays typically indicate a leisure trip, when travelers choose where they're staying. A decline in Saturday-night hotel stays in those border markets meant people weren't making that leisure trip.

“It becomes their sense of civic duty to stay in Canada, to remain in Canada and spend their Canadian dollars with Canadian service providers," he said. "I'm afraid what we see today — decelerations in room demand along the Canadian border — is just the beginning of slower, declining demand numbers in those areas for the remainder of the year and maybe for years to come.”

Walking a familiar road

For Offredi, who said groups have canceled conferences at her hotel both in the short term and for later this year, the feeling is all too familiar. She's seen this trend before — in 2020 as the pandemic immediately affected travel — but wonders how far the effects will last this time.

For now, she finds some comfort in the volatility of some of the Trump administration's trade policies.

“We're going down this really ugly road, but it could change at any moment. I don't feel like we're doomed. I feel like we have to be flexible and be ready. This is going to be fluid over four years, unless something drastically changes," Offredi said.

What's been particularly gutting for Offredi is the potential year she's lost. She said she had hoped to finally be closer to or even surpass 2019 numbers after years of climbing out of the hole the hospitality industry fell into in 2020.

“When the pandemic happened, [we were told] it could be anywhere from a three- to five-year recovery period. Here we are at five years … and there's no way we're going to make up what we've lost in our first quarter,” she said.

For now, Offredi has not yet made major personnel changes, but she has had to start making other cuts where she can.

"Really, all we can do is buckle down on our expenses," she said. “I have the staff coming to me asking, ‘are our jobs in jeopardy?’ And at this point they're not, but the hours are. You can only support the labor for the business that we have. We thought we'd be busier this time of year, so we have more hours technically scheduled that we've had to reduce."

Bigger picture

So far, the pandemic comparison is confined to border markets like Bellingham, which has posed an extra challenge for hotel operators like Offredi. She said her hotel's owner — Mount Vernon, Washington-based Hotel Services Group — is local and understands current conditions. On the brand side, she's had to communicate what's happening on the front lines.

“I think there is some education component that needs to be seen in order to make sure that your management, your ownership, knows what's going on specific to our area and other markets like ours," Offredi said.

While Offredi and her staff are plunged back into what 2020 felt like, most of the rest of the country might not feel a difference, Freitag said.

"On a larger scale, if you step back, the impact on the U.S. hotel industry is going to be muted," he said. "I don't want to make light of that, but the big picture is that those numbers will be disproportionately affecting where the Canadian travelers are going. If it's not of the top 25 markets or one of the border states, you may not see the impact."

Freitag pointed to Marriott International, which reported that only around 2% of U.S. room demand is from travelers from Canada and Mexico. Other brands report similar specifics, he said. Freitag posited that come autumn, when it's time for "snowbirds" who travel to warmer destinations through the winter, Canadian travelers will fly right over the U.S. and opt for Caribbean destinations instead.

Sending a message to Canadians

While Canadians have varying attitudes about travel to the U.S., Offredi says there's also an element of fear for them.

"People are scared to cross the border," she said. "The unknown is really what’s creating more of the fear.”

Additionally, one of the big attractions for Canadians visiting the area is shopping. Offredi said she's seen guests drive over to visit their favorite U.S. stores — like Trader Joe's or Costco, for example — spending hundreds of dollars stocking up on items, only to be asked to pay another $100 in tariffs and exchange rates.

"They're literally going back to Costco and returning their [shopping]," she said.

Offredi, who serves as a member of the Bellingham Whatcom County Tourism board, said the community has come together to work on a campaign to tell Canadian travelers that despite the growing hostility from the country's executive office, they are more than welcome.

“We are trying to put out a cohesive message that is just letting the Canadians know that, 'We want your business. We want you here. We aren't doing anything personally to make it hard for you to travel,'" she said.

Because Offredi knows all too well reflecting just five years ago what it's like to not have Canadians traveling to the U.S.