The second article from my Hospitality Historiography series is about Joseph Lee. During late 19th Century, Joseph Lee became one of the most well-known African-American hotel proprietors and restaurateurs in New England. Lee was not only a brilliant entrepreneur; he was a true hotelier (along with his wife Christiana) and a “master of hospitality.”

More than that, Lee was a man of constant curiosity and innovation. Lee’s story not only demonstrates the significance of these essential leadership qualities; it also shines a light on how critical resilience and perseverance is to navigate a volatile and disruptive environment — just like the one we’re currently operating in today.

Joseph Lee was born on July 29, 1849, in Charleston, South Carolina, to enslaved parents Susan and Henry Lee, a blacksmith. Not much is known about Lee’s childhood years. Lee began baking as a child working in a kitchen, most likely acquiring his culinary skills from his mother, who served as a cook. Lee also worked in a bakery in Beaufort, South Carolina.

Lee came to Massachusetts shortly after the end of the Civil War, but soon joined the United States Coast Survey. For the next decade, he honed his culinary chops and knowledge onboard ships, providing meals for the crews.

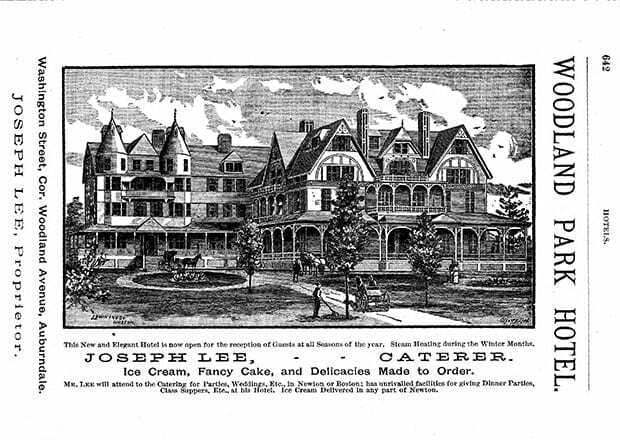

On May 12, 1875, Joseph Lee married Christiana Howard, a schoolteacher in Philadelphia. The Lees made their way to Massachusetts in 1877, where he opened the Hillside House at Weston. After that, he managed the Bellevue in Wellesley Hills until he was offered the job of managing the new Woodland Park Hotel in the Auburndale section of Newton. In 1882, Lee leased the Woodland Park Hotel. One year later, he was able to purchase the property.

The Woodland Park was just a summer hotel at the time, standing in the middle of a sand bank. Over the next several years, Lee enhanced the surrounding landscaping and grounds, added a new annex to the property; added a billiards room, bowling alleys and 70 more guest rooms.

The elegant Woodland Park Hotel was open to guests throughout the year, and provided incomparable facilities for hosting lavish suppers, dinner parties and other social activities. Lee also delivered ice cream, fancy cakes and delicacies made to order from his hotel to all areas of Newton. Lee provided catering services for parties and weddings, in both Newton and Boston. During the summer of 1885, in addition to the Woodland Park, Lee managed the Fort Point House, an upscale family resort on Cape Jellison in Stockton, Maine.

By 1886, Lee had become one of Newton’s richest businessmen. The Woodland Park Hotel was well-respected and catered to distinguished guests and prominent members of Boston society and political figures including President Benjamin Harrison and his family, President Chester A. Arthur and President Grover Cleveland.

In 1891, Lee became owner and operator of the Hotel Abbotsford, in Boston. The Italian Renaissance property had a restaurant that Lee could make his own. By this time, Lee had rightly earned his reputation as one of the most successful proprietors and hoteliers in all of New England. People loved Lee for his exceptional culinary skills and hospitality expertise.

Due to the Panic of 1893 and subsequent economic depression, Lee faced a severe hardship. As a result, he was forced to relinquish his ownership of the Woodland Park Hotel and Hotel Abbotsford businesses in 1896.

Lee, a man of determination and resilience, could not stay away from the hospitality business for long. In July 1897, he opened the elegant 250-seat Pavilion Restaurant overlooking the Charles River and Norumbega Park. He stayed at Norumbega Park for only one season as a new opportunity developed in Quincy, Massachusetts. By 1897, Lee and his family had relocated to Boston, where he continued to attend to his thriving catering business — the Lee Catering Company.

Also an inventor, Lee became interested in automating the process of making bread. He wanted to reduce the time and effort it took to knead dough by hand but also ensure consistent quality. In August 1894, he acquired a U.S. patent for his bread-kneading machine, which was intended for use in hotels and large homes. The innovation was far more efficient and ensured a uniform quality in the bread.

Lee Catering Company could bake hundreds of breads daily that would have taken a dozen workers to produce. But soon thereafter, he realized he had a good problem on his hands. The machine was producing too much bread. So, in June 1895, he secured another U.S. patent for his bread-crumbing machine which transformed day old bread that would have been discarded into a useful ingredient — a coating for chicken or fish. The immediate success of the bread-kneading machine made Lee a very wealthy man.

Lee came to Squantum in 1898, where he owned and operated an upscale 16-room hotel and summer resort in Squantum, located on five acres and overlooking Dorchester Bain the northernmost section of Quincy, Massachusetts, called Squantum Inn. At the grand opening ceremony on July 30, 1898, a “who’s who” of local politicians and capitalists, including then-Mayor Sears of Quincy, were in attendance.

Squantum Inn was visited by numerous Massachusetts politicians and President Theodore Roosevelt. Customers found Lee’s hospitality irresistible. Diners could view the fish and game on hand, make their selection, and have it prepared cooked to order. Lee fried his fish with a coating of breadcrumbs that guests found superior to the coating of crumbled crackers most chefs used at the time.

Lee assigned the patent rights to the National Bread Company for ownership in the company and royalties in 1901. The National Bread Company was backed with $3 million in investments (approximately $104.8 million in value today), and Lee was made a stockholder.

Lee sold the rights to his bread-crumbing machine to the Goodell Company, a New Hampshire-based manufacturer. The machines were then mass-produced by the Royal Worcester Bread Crumb Company and marketed to hotels and restaurants nationwide.

By the turn of the century, Lee’s bread machines could be found at America’s top hotels and were a fixture in many of the leading catering establishments across America.

Lee managed the Squantum Inn for a decade until his death at this home of pulmonary tuberculosis on June 11, 1908, at the age of 59.

Within a year of his passing, Lee’s wife Christiana purchased the Pratt estate located around the corner from Squantum Inn. In June 1909, with the help of their daughter Genevieve, she opened a restaurant similar to the Squantum Inn in memory of her husband and named it Lee’s Inn.

Christiana managed Lee’s Inn, with the help of her daughter Genevieve until she died of heart disease on Feb. 9, 1916, at the age of 65. Christiana’s passing ended 18 years of the Lees’ association with Squantum and 40 years of unrivaled customer service and hospitality.

In 2019, Lee was inducted into the American National Inventors Hall of Fame, a century and quarter after he received the first U.S. patent for his revolutionary bread-kneading machine.

Calvin Stovall is a keynote speaker, author and hospitality historian with ICONIC Presentations, LLC. He has nearly 30 years of experience in the hospitality, including as a front desk clerk at the Holiday Inn City Centre in downtown Chicago and vice president of brand marketing with Hilton.

The opinions expressed in this column do not necessarily reflect the opinions of Hotel News Now or CoStar Group and its affiliated companies. Bloggers published on this site are given the freedom to express views that may be controversial, but our goal is to provoke thought and constructive discussion within our reader community. Please feel free to contact an editor with any questions or concern.