From time to time over the years, educator Mike Oz would watch teenagers jostling elbow-to-elbow through the crowded hallways at the Oakland School for the Arts and wish he could travel back in time.

“I’d think, if only we could go back to 2008 and buy something when we had the chance,” said Oz, executive director at the public charter middle and high school that’s produced Oakland-born celebrities like film actress Zendaya and Grammy-nominated singer Kehlani.

Oz was not the only Oaklander in those years to feel a sense of real estate nostalgia for a time before technology workers flooded the Bay Area’s second city as a cheaper, more diverse alternative to San Francisco, filling the bars and driving up rents in and around Oakland’s commercial center. In the years before the COVID-19 pandemic, companies such as Uber and the then-named Twitter, now X, bought or leased office space in the onetime theater district known as Uptown.

Now the post-pandemic landscape is offering a second chance for a new wave of investors. Nonprofits and entrepreneurs who were effectively priced out of their own neighborhoods see a pathway to gaining a long-term foothold in urban centers across the country. As institutional and private equity buyers have pulled back, owner-users have pounced on the once-in-a-generation opportunity to acquire real estate at deep discounts across the country, with sale prices down 50% over the past two years.

Arts-related nonprofits are taking a more direct interest in real estate nationwide in an effort to preserve their long-term livelihoods and communities. Cities have looked to creative districts, often drawing people and foot traffic after office hours and promoting a sense of community, to bring back struggling downtowns in the post-pandemic era.

Cleveland, for example, has a $12 million annual fund generated from a cigarette tax that's directed to arts funding, supporting efforts like the revitalization of Playhouse Square, turning "a neglected area with abandoned theaters to the second-largest theater district in the United States," according to the San Francisco Bay Area Planning and Urban Research Organization, a public policy research group. Philadelphia, meanwhile, operates the nation’s largest mural arts program, while the city's cultural fund grants $3.6 million each year to 260 arts organizations, "contributing to the city’s vibrant cultural life and aiding in its economic recovery following the pandemic," according to the Bay Area research organization.

To be clear, the investment amounts are small and the direct effect can be limited. But the creative funds can encourage developers and property managers to explore the adaptive reuse of vacant office space for creative tenants, according to a January 2025 report from the group, and prompt further change in areas where demand is low.

Investing in arts districts "will not resolve all of the challenges confronting downtown districts in Bay Area cities," the report said. But funding in such areas "can restore or strengthen communities, support existing businesses and institutions, and create opportunities for new attractions that bring more visitors and investment to the region’s urban downtown centers."

Ownership goal

In the tech-heavy Bay Area, home to some of the country’s highest-demand real estate markets a decade ago, arts-related groups like the school have seen what can happen to small businesses and other players who don't own their own buildings when a neighborhood gentrifies.

“What downtown Oakland looks like 30 years from now is really dependent on the real estate transactions happening now,” Oz said.

The school is raising funds in hopes of finalizing its first real estate purchase, the Dufwin Theater, a nearly century-old former movie house turned 63,000-square-foot office property, for $9 million — about half the asking price floated by its owner just last year, according to Oz.

Much of the approximately $500,000 the school needs to raise to finance the initial payments for the property is coming from families and community members. "It's really daunting, but we'll do it," Oz said. "We have to."

The vacant office building’s open floor plans are ideal for the school, which needs to expand from its current main campus in the landmark Fox Theater building around the corner, where its 800-plus students are crammed into two floors — with some teachers forced to share classrooms — with no outdoor space.

The school plans to stay at the city-owned Fox but use the seven-floor Dufwin Theater building as its primary arts instruction space, while perhaps adapting the roof garden as a teachers lounge, Oz said.

Arts-focused property

The 1928 building's twisty history mirrors the ups and downs of the neighborhood.

The Dufwin was built to house a live theater troupe and later underwent a conversion to a movie house. Embarcadero bought the building out of receivership for $8.4 million in 2016, investing another $10 million in upgrades and rebranding the building as the 519 Uptown with plans to lease the office space to a start-up in 2019, plans that never panned out.

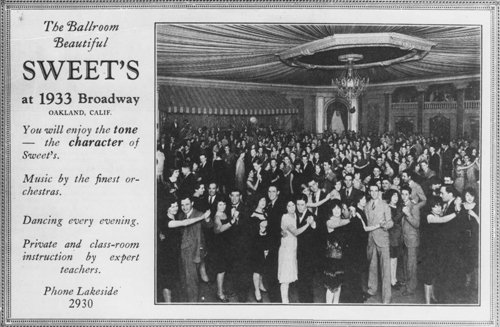

That setback appears to have been a blessing for the school. It has long functioned within a hodgepodge of leased spaces in often run-down venues left over from a vanished era. Theater students rehearse at Sweets Ballroom, a popular World War II swing-dancing venue that later hosted jazz greats such as Duke Ellington and Count Basie. Across Telegraph Avenue, the music department has converted a former variety store, J.J. Newberry’s Five and Dime, into a student practice space.

While noting the important symbolism of those historic arts venues, "we are still at the mercy of rising rent prices, private landlords and dilapidated buildings," Oz said.

The school — founded by then-mayor and former California governor Jerry Brown in 2002 — moved into the newly restored Fox Theater building in 2009 as part of a multiyear, multimillion-dollar redevelopment effort by developer Phil Tagami and a group of concerned citizens. The Friends of the Oakland Fox hoped the reopening of the iconic theater would spearhead a revitalization of a neighborhood that one theater employee then described as “fairly desolate."

By 2015, the neighborhood had transformed into a fashionable destination. Office vacancy rates in Oakland’s central business district dwindled to about 6%, as start-ups escaping San Francisco’s stratospheric rents staked out space. Developers scrambled to build luxury apartment towers to accommodate the influx of high-earning professionals.

Since then, downtown Oakland has changed yet again, as its commercial center has struggled to bounce back from the effects of the pandemic and remote work, with dozens of stores and restaurants closing after contending with rising crime and declining foot traffic. Office vacancy in downtown Oakland, the East Bay's core business district, is at a record high of 19.2%, above the 14% national average.

In November, one of the city’s largest employers, Kaiser Permanente, announced plans to “significantly reduce” its footprint in Oakland. Absorption, or the net change in occupancy measured by the amount of space occupied vs. vacated, in 2023 fell to its lowest level in about 25 years, according to CoStar data, with tenants collectively handing back nearly a million more square feet than they leased.

Once-in-a-lifetime deals

A handful of investors who are convinced that Oakland will soon boom again are taking advantage of the reset, stepping in to nab properties that have attracted little interest from big institutional investors at breathtaking discounts.

For others, the current moment is a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to stake out a long-term home in a neighborhood that a few years ago seemed out of reach, even to those who had helped build it.

Oakland City Councilmember Carroll Fife said the past few years have seen Black-owned businesses trickling back to downtown Oakland as rents have fallen dramatically, a notable trend in a city that was nearly 50% African American in 1980, a percentage that had dwindled to about 20% by 2020, according to U.S. Census data.

Fife noted that the arts school has one of Oakland’s most diverse student bodies. She sees the school as continuing an Oakland legacy that harks back to the days when people flocked to the clubs on Seventh Street in West Oakland to hear James Brown or Aretha Franklin and when muralists forged a tradition of bold community art.

“One of the primary ways Oakland is known is for its arts scene,” Fife said. “Just across the board, this city has nurtured some of the most iconic artists in the world.”

She and Oz are among those hoping to revive that legacy by establishing an arts and entertainment corridor that some hope could also help reverse a perception that has deepened since the pandemic that downtown Oakland is dangerous. A looming budget deficit and a mayor who was recalled last year amid federal bribery allegations have not helped.

'Face of Oakland'

Hoping to change that image, a group of business owners, officials and community members including representatives of the school have begun meeting monthly at the Fox Theater under the leadership of Tony Leong of Another Planet Entertainment, the theater’s longtime general manager. Leong said the Fox and the historic Paramount Theater a few blocks away have “kind of become the face of Oakland,” particularly as the city has lost all three of its professional sports teams in recent years. Both venues host regular live acts from stand-up comedians to symphony performances.

“We have a lot of things to offer that not many other cities have anywhere else in the Bay Area or the whole state,” Leong said. His group has pushed ideas including flat-rate $5 garage parking for evening showgoers to partial street closings and food trucks. The idea is to encourage people to patronize restaurants, bars and small entertainment venues that have struggled to remain open in the wake of crime concerns.

A business coalition in 2023 floated a plan called Market Street Arts that aimed to turn around San Francisco’s beleaguered Mid-Market neighborhood, another historic theater district, using a mix of public and private money to help arts groups fill vacant storefronts and enliven public spaces.

A historic 50,000-square-foot office building adjacent to Market Street’s legendary Warfield Theater will become a hub for arts and independent groups after recently selling at a deep discount to the Community Arts Stabilization Trust, a San Francisco nonprofit that helps connect arts and culture groups with affordable spaces. The group was formed in 2013 as artists and nonprofits were rapidly getting priced out of the Bay Area as real estate costs soared.

Ken Ikeda, the group’s CEO, said the recent real estate reset has prompted communities to reevaluate the value of arts and cultural institutions and their crucial role in building sustainable neighborhoods by drawing people together.

“This is such a unique moment,” Ikeda said. “It’s wonderful, because we feel seen. But we also feel a lot of urgency because we understand that it won’t last.”