To embark on an intensive restoration of a property based on hand-drawn maps from the 1800s, you must be passionate about historic preservation. And patient. Depending on who you ask, maybe even a bit possessed.

Veteran craftsman Larry Lof is at least two of those things.

Several years ago, the retired professor gambled on a peculiar retail property in the southernmost border town of Brownsville, Texas. As Lof persistently peeled back layers of crudely applied cladding from the building he purchased, he was thrilled to uncover the remains of a distinct Mexican Revolution-era architectural style now threatened by extinction.

Exemplary of the “border brick” motif, the small, indoor-outdoor estate blends old-timey New Orleanian and Mexican characteristics, featuring a French Quarter-inspired balcony overlooking a mud-borne courtyard.

After years of renovation, the space will soon become the administrative hub of family business NVS, a property services contractor expanding to better serve the federal government. NVS is a “people business,” owner Nick Soto Jr. told LoopNet. When the firm outgrew its warehouse on the edge of town, Soto chose this new airy abode "for his people."

A Revolutionary Restoration

Brokering the deal for Soto was his friend Fernando Ballí of the Brownsville-based Ballí Group. Seemingly making it easy for everyone involved, Ballí attributed the heavy lifting — literally — to his “mentor” Lof.

Lof already had dozens of historic renovations under his belt by the time 1244-46 E. Washington St. came on his radar. To discover his latest project, he had to peer through a portal in time.

Where everyone else saw an aluminum-clad eyesore blending in among other dilapidated downtown storefronts, Lof saw an opportunity to reclaim history. His research began when he noticed the tip of a parapet peeking out atop the stained slipcover of a vacant used clothing store. If there was a historic building buried under 21st-century crust, he needed to know just how old it was.

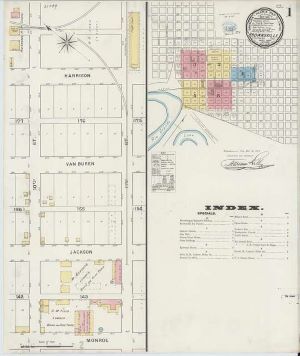

But not much information was available beyond a 1927 aerial photograph. It was only by pouring through volumes of old Sanborn maps that he gained traction. Beginning in Civil War times, the Sanborn Map Co. platted meticulously detailed lithographic accounts of cities and sold them to fire insurance companies. Now, the archives are available through various sources, including the Library of Congress, and they’re known to be a treasured tool for the discovery of historic preservation projects.

The building wasn’t on an 1877 map, but it appeared in an 1882 edition, and it matched the footprint seen on present-day satellite imagery. “That’s how I knew when it had been built,” the unassuming Lof told LoopNet. With that context, he was able to confirm accounts that the property had once been what historians identify as the Star mercantile store and attached residence of proprietor Solomon Ashheim.

The property’s architecture speaks to Ashheim’s journey to Brownsville by way of New Orleans, a common route for his cohort of immigrant businessmen from Europe. “South Texas had no overland connection to Austin and San Antonio,” Lof explained. “Everything came and went via a steamboat or sailing ship through Galveston to New Orleans.”

Distinct to Brownsville, the border brick vernacular blends two traditions. Constructed with mud from the Rio Grande Valley, border brick buildings feature a demure, Alamo-style courtyard, but they’re often adorned by the Victorian flourishes of New Orleans’ French Quarter. Making this example somewhat unique, the residential portion of Ashheim’s property was laid out like a quintessential “Charleston single house” begging for a breeze with its porch side running perpendicular to the street.

Beyond surface-level design, the connection to Ashheim also deepened the building’s intrigue. A history book on the Mexican Revolution, which left an indelible mark on Brownsville, shines light on how Ashheim’s property was caught between the two cultures that inspired it. According to “Century of Conflict,” several men had been staying on the lot when Ashheim purchased it for development. Hiding out from the French Imperial Army, the men were later identified as a group of Mexican generals that included Porfirio Diaz, who went on to be president.

Banking on Baked Bricks

But Lof didn’t get too caught up in the lore. Before the dust from the history books and old maps settled, he began asking if he could look around the empty store. He saw jogs in the wall and evidence of where footings would be. “It was submerged, but I knew the original building was still there,” he said.

“I told the property owner I was interested. He gave me a price and I wrote him a check.”

That price remains undisclosed, but Ballí indicated it was a steal considering what Lof was able to do with the property, although he stressed that Lof’s game isn’t about flipping properties for profit.

The question for Lof was, “How do I rescue this building from the changes that occurred in the mid-to-late 20th century?” Built before electric lights, air conditioning and fans, border brick buildings relied on open spaces. But as downtown square footage became more and more valuable, one of the property’s previous owners had at some point deemed the patio, balcony and cast-iron entry corridor all inefficient uses of space. “They closed it all in, then divided the combined space into three stores spanning a 50-foot frontage typical of a downtown lot,” Lof explained.

Demolition was necessary, but it wasn’t first on Lof’s agenda. Working with a structural engineer-turned-contractor with whom he’s had a decades-long partnership, Lof started peeling back the layers slowly — eschewing a formal plan in favor of a day-by-day approach.

“Most contractors shouldn’t even try a historic rehab,” he said. “The ones who have all know it can be very expensive, because it doesn't matter how good your initial analysis is — you’re going to run into surprises. So we make decisions every single day based on what we find.”

Fortunately, they found clues. The first misstep on many rehabs is having contractors rush in and clear out debris, Lof said. “They throw away all the evidence: the old windows, the old doors, the frames and even planks of wood. But those are the artifacts that tell you how the building was constructed.”

Though he was a biology professor by day, Lof put on his archaeologist hat for this project. Having purchased the property in the summer of 2019, Lof spent much of the pandemic era at the site, studying the craftsmanship of what was left behind.

It helped that he knew what he was looking for. Lof had been an apprentice of some remaining “old maestros” in the 1960s and ‘70s, he said. "The types of craftsmen who understood how historic structures were constructed before the machine age and who still did everything by hand themselves."

The process of replacing doors, windows and even the mortar holding up the walls all had to honor the craft used to bring the building to life nearly a century and a half ago. “The formal etched-glass entrance to the residence, for example — I had pieces of the originals that had been stashed in the back of the building; and I had some photographs of the originals,” Lof said. “From that, I was able to identify the details and remake what I needed to reestablish the exact same feeling.”

You can’t use modern commercial building materials to sturdy up the bricks either, he said. “It’s too hard; it would destroy one of these buildings. You have to use soft, hand-made mortar.”

Historic and Best Use

That said, Lof doesn’t consider anything too precious. “Restored historic buildings can’t always just be museums,” he said. “Or worse, mausoleums. You have to find an efficient use.” Reading the market, Lof revived the building to be used in the way it was in its original proprietor’s day: with a small residence adjacent to the back courtyard and a large, main storefront component facing the street.

He didn’t initially envision it as an office. But the 5,868-square-foot, two-story layout can be easily adapted, Lof said. That’s where Ballí came in, imagining how this one-of-a-kind space could be made into a bespoke office for Soto’s administrative staff.

“I provide labor to the U.S. government. The product that I’m selling is my staff,” Soto said. The new spot will be the hub for about a dozen employees in human resources, payroll, accounting and more who do “everything that we need to do to support our staff,” he said.

“If I can make them feel good about where they work, then the level of service that comes with that is improved and it helps us get more projects and add more employees.” The workplace will also host new internships akin to the type of opportunity that Soto said made it possible for him to get to where he is today.

And it’s certainly an upgrade. Until moving to the new space this month, NVS worked out of a nondescript shell space on the fringes of town. “It’s a warehouse,” Soto said. “It’s my maintenance office and it has some offices — but we’ve outgrown it; some of my staff has been working on the floor with their laptops.”

A Small Business Loan Tailored to Big Dreams

When Soto approached lenders about mortgaging the renovated property — which he ultimately acquired from Lof for $775,000 in August of this year — Soto said the bankers were “blown away” by the before-and-after photos he showed them.

Soto himself was blown away by the financing he landed: a 25-year, fixed-rate SBA 504 loan that required only 10% down.

Through the SBA 504 program, the U.S. Small Business Administration finances 50% of the commercial real estate purchase; a local bank lends 40%; and the remaining 10% equity comes from the buyer, which must be an eligible small business. Administered by Certified Development Cos. — in this case, a CDC called the Business Development Fund of Texas — these loans can be lifelines to small but growing businesses like NVS.

Without the help of the federal government, Soto would have had to use his working capital to come up with a 25% down payment for a traditional loan, explained Daniela Sosa, executive director of the Business Development Fund of Texas.

“Small businesses interested in purchasing a building should know that the federal government is here to help,” Sosa told LoopNet.

Even better if it’s in a historic district, she said. “A lot of people think, ‘man, it's a historic building, I'm going to have to invest so much.’ But knowing that they could get the property with only 10% down really makes a difference. And we’re able to finance not only the purchase of the building, but also the renovations.”

Renaissance in Historic Real Estate

Now that he has his certificate of occupancy, Soto plans to register the renovated property as a historical marker. They are getting used to that spirit in Brownsville, as this project exemplifies “the paradigm shift” led by Lof and others in bringing the historic enclave’s past into the present, Soto said. That renaissance includes buildings like the Majestic Theatre around the corner from the property, which Soto visited as a kid "back when movies cost a quarter.”

The Majestic was purchased by the University of Texas System in November for redevelopment into a performing arts center. “This was considered a blighted area,” Soto said. “But now there’s a real chance for real estate investors to renovate Brownsville's historic buildings — which in number, are second in the state only to San Antonio — and create new, nice facilities, restaurants and stores.”

Hopefully more redevelopers make use of historic tax credits, Lof added, lamenting that he had not been able to take full advantage of all the historic renovation incentives available on this particular project. A lack of knowledge about how the incentives worked meant that very few were using them until recently. Now, he’d consider himself foolish to not at least try to capitalize on any such programs.

As Soto and company settle into their new digs, Lof has his eye on another “dig” — and it’s a project that some people might not expect, he said. “The easy ones get picked up and they’re done pretty well,” he concluded. “But I like the ones that have been lost and submerged; the unique ones that are too weird for everyone else. The ones that are really worth bringing back, because if they’re not … their particular style, and the craftsmanship used to build them, could be lost forever.”