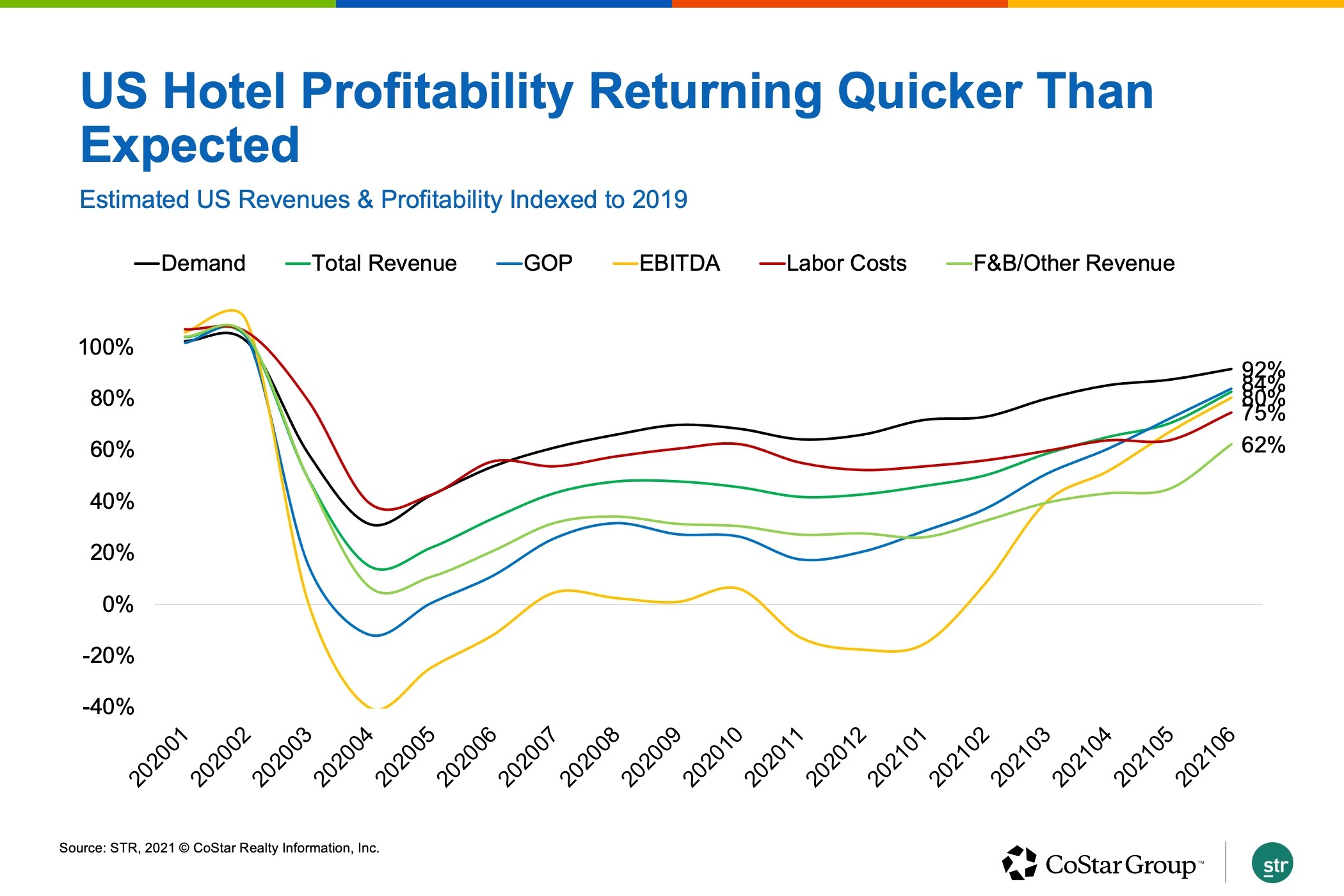

Hotel profitability has come a long way since the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic, and particularly in the past few months, according to data from STR, CoStar's hospitality analytics firm.

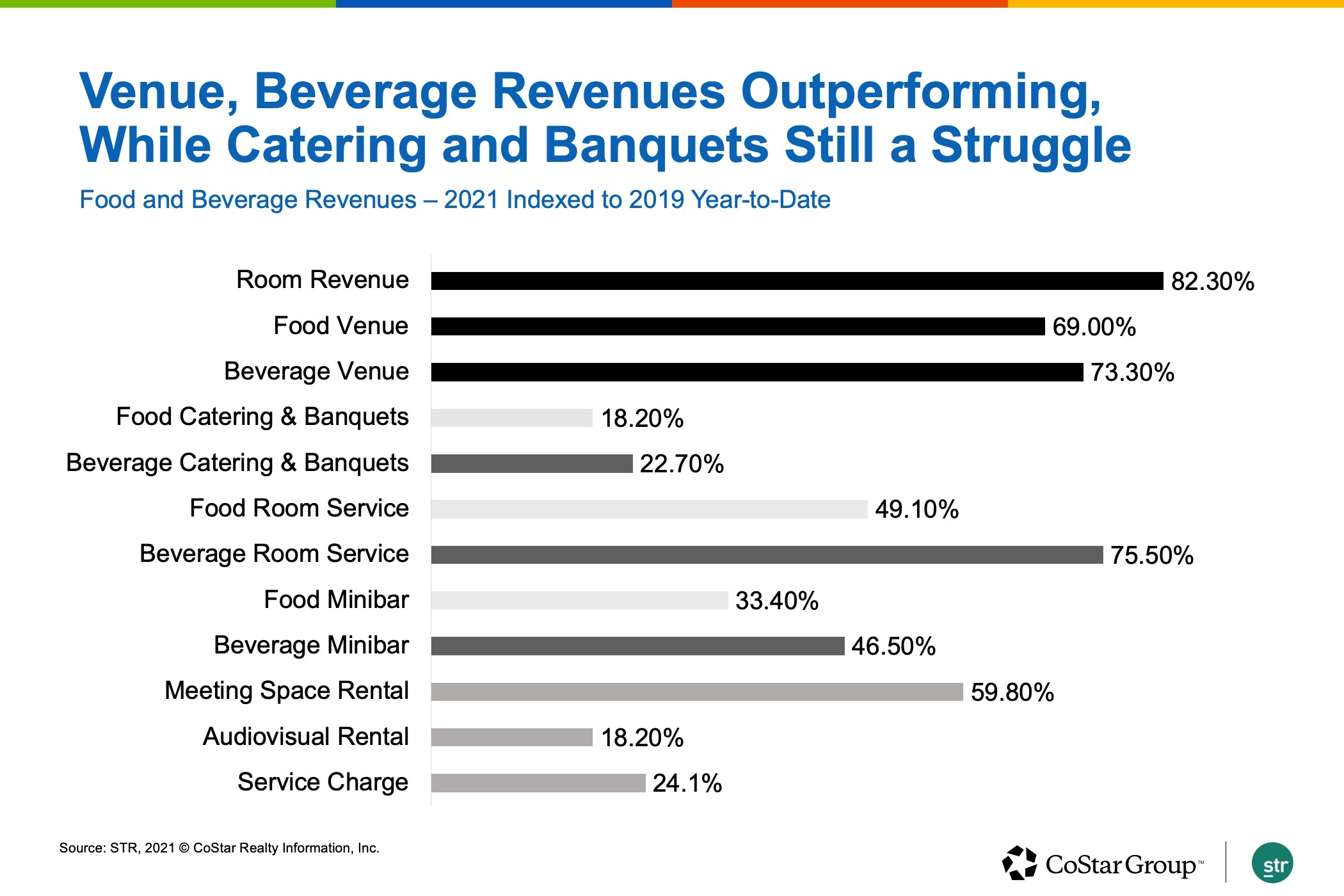

Trends in U.S. hotel industry profit-and-loss data reveal that food and beverage revenues are still "slow to come back," and are at only about 62% of 2019 levels year to date, said Joseph Rael, senior director of financial performance at STR, who presented during the "Pushing the P&L Reset Button" panel at the Hotel Data Conference.

Beverage revenues — principally from the hotel bar — are outpacing food revenues in the recovery, and are nearly two-thirds of what they were in 2019. The real laggard in the food-and-beverage department is catering and banquet revenue as it suffered from a lack of group business during the pandemic.

Hotel room revenue, meanwhile, has risen in line with hotel demand, and is at 82% of 2019 levels year to date, the STR data shows. Total revenue is at about 84% of 2019 levels.

But revenue is different from profit, and while the data demonstrates some success in curbing costs, fixed expenses continue to drag down gross operating profits in the U.S. hotel industry. Year to date, gross operating profit per available room is down 70% from 2019 levels.

Much of the cost savings that hotels have achieved have come from the labor side, as restaffing amid a labor shortage has been a challenge.

Labor costs at U.S. hotels year to date are at about 75% of 2019 levels. That cost has risen since the start of the pandemic, in parallel with the rise in hotel demand, though there is still a considerable gap, Rael said. Hotel demand year to date is at 92% of where it was at the same time in 2019.

"We've seen labor costs typically decline at about half the rate that revenues do so. Of course, this is a little unique. We're seeing a lot more declines in occupancy this time around, and so that's where we're seeing stronger declines in labor costs," he said.

The return to profitability hasn't been even across the U.S. hotel industry. Full-service hotels — in the luxury and upper-upscale segment — have struggled more while having higher cost structures to overcome than select-service hotels, as well as independents, which have more flexibility with cost cutting.

Presenting with Rael, Priya Chandnani, vice president of revenue management at Benchmark, said her company's heavily independent portfolio had the advantage of operating lean to begin with.

"As we were starting to think of the pandemic, what was the fluff or fat ... there's very little," she said. "And then just pivoting from the loss of group [business], which for my portfolio was pretty significant. Replacing it with the leisure segment was certainly one thing that kind of helped offset some of that demand change."

To make up some of that lost catering and banquet revenue, Benchmark pivoted to an expanded grab-and-go food and beverage operation and customized menus and packaging options.

Still, early in the pandemic, Benchmark made the decision to temporarily close some of its hotels, based on analysis of the level of occupancy required for each property to break even.

"We did the whole break-even analysis, worked very closely with our finance teams to really get to that point of ... if we were to lean out all of the expenses, what is that break-even point? And then had to make the hard decision to close the hotel. The good news is we all stayed tracking demand trends, so as soon as we started seeing an uptick, we were very quick to say, 'OK, it's time to start opening them back up.' We did close, for a period of 30 days, a majority of our hotels, but by May 1, a majority of them had opened back again," Chandnani said.

STR data shows that break-even occupancy decreased during the pandemic, largely as a result of cost reduction, and on average, hotels could operate without a loss at 40% occupancy, Rael said.

Furthermore, the cost of keeping a hotel open during the pandemic was not much greater than maintaining a closed one.

"The difference is, those hotels that stayed open were able to actually drive revenues," Rael said, though "they still actually lost money on a [gross operating profit] basis. But, of course, for the closed hotels, that's all lost."

Chandnani said "one silver lining" of the pandemic is that "it has helped us get even more efficient that we previously thought [possible]."